A photographer uses various levels of involvement while capturing an image. The elements of a photographer’s involvement may include: depictive involvement (concerned with basic, factual description above all else); constructed artistic involvement (the subject matter is created by the photographer or under the photographer’s direction); representational artistic involvement (no manipulation from the photographer); or directed reality involvement (the photographer works in tandem with what already occurs in the view). The amount of a photographer’s participation within a scene, from strictly representational to highly constructed, not only affects the category or genre of the work but also its classification as a depictive document or a photographic art piece. Depending upon the ratio of the photographer’s involvement to the reality of the scene, directed reality involvement can be less obvious and difficult to categorize than the other methods. Ultimately, since there is not a clear division between this category and constructed reality involvement, the differences between the two can be ambiguous.

My curiosity about influences concerning various generations of artists and photographers motivated me to delve deeper into this subject. I have chosen two photographic artists who exemplify directed reality involvement: Saul Leiter’s work from the mid-twentieth century and the work of the contemporary photographer Todd Hido.

Though Saul Leiter’s (American, 1923–2013) work was recognized by the photographer/curator Edward Steichen and exhibited at the Museum of Modern Art in 1953, he remained essentially anonymous for most of his career. Originally a painter, Leiter discovered photography as an additional artistic outlet for his creativity. During the 1940s, “straight” or street photography was becoming critically acclaimed, as the work of photographers such as Robert Frank and William Klein offered visceral views of urban life. As a painter, Leiter found inspiration with street photography; he used his camera as an extension of his mind, arm, and paintbrush.[1]

Leiter’s work embodied an alternative view of street photography: instead of black-and-white film, Leiter used bold chromogenic (three-colored) color film and, with his unique style of composition and framing, offered a creative twist within the reality of city streets. He used his camera as an unconventional way of seeing, framing, and communicating events on the streets of New York City by shooting through obscure angles, under canopies, or through rain-soaked store windows. The printed work offered a realistic view of the city with a slight bend of stillness, gentleness, and grace.[2] Leiter loved beauty, and this love resonates in the piece below. Leiter’s only directed involvement was to stand behind a rain-soaked window; in doing so, he created an image that offers a softer version of the cold reality outside on the busy New York street. The window acts as a filter to the harsh reality of the fast-paced city life outside. The lovely pop of yellow color is juxtaposed against a nearly monochromatic scene, softening the reality of the cold winter day. Upon further study, it appears Leiter’s directed reality involvement has a nearly 50–50 ratio: half-illusory, half-real.

[1] http://www.gallery51.com/index.php?navigatieid=9&fotograafid=15

[2] http://www.newyorker.com/books/page-turner/postscript-saul-leiter-1923-2013

Snow | 1960 | Saul Leiter

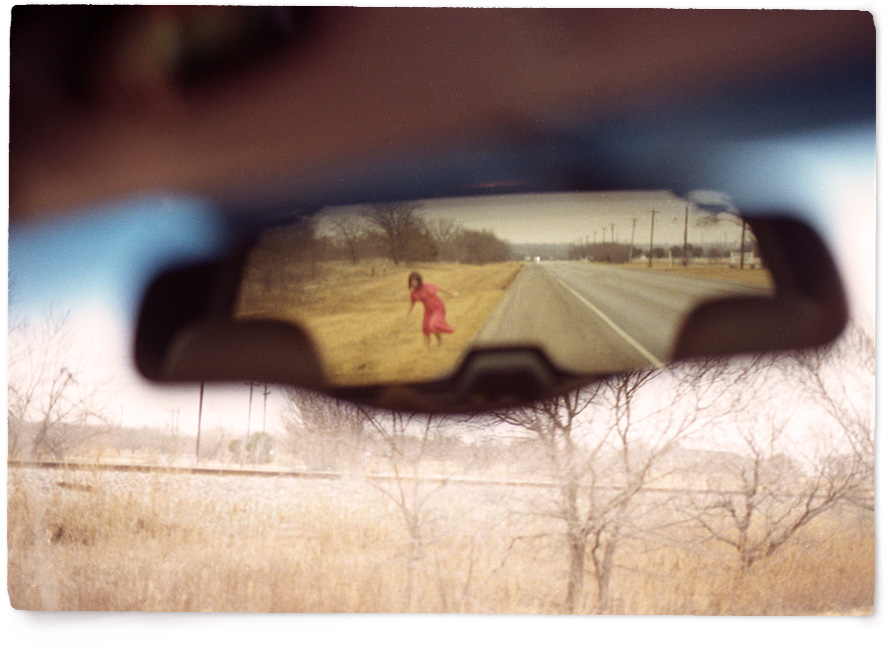

Whether influenced by Saul Leiter or simply on a remarkably similar path, Todd Hido (American, b. 1968) offers a similar directed reality involvement in two of his series, entitled A Road Divided and Excerpts from Silver Meadows. Hido has never used filters on his Pentax 6x7 camera’s lens; instead, he often uses a rain-soaked car window as his filter between the lens and reality. Adding this element to his syntax enhances a supplementary, illusory layer to the narrative. After finding a location or scene to photograph, Hido’s approach often includes sitting in his car and photographing rain accumulating on the windshield. In addition to the scenery, the weather ultimately becomes a prominent subject throughout both series, often inferring an emotional weight. Hido’s directed reality involvement and inclusion of the windshield creates a murky effect, resulting in an antiquated veneer to the finished images.[3]

Hido’s images below are views of deserted scenes on dreary days. His use of directed reality involvement offers a unique and experimental way of observing an ordinary landscape. Through his own direction, Hido chooses at which point he will release his shutter, after deciding how much of the rain-soaked windshield he wants to include within the view. Therefore, he purposely interferes with the clarity and reality of the setting. This twist on reality offers a distinct and moody perspective; the “through-the-windshield” landscapes suggest the forlorn viewpoint of a perpetual outsider.

[3] https://paddle8.com/work/todd-hido/30270-10845-7

Untitled #10473-B | 2011 | Todd Hido | Chromogenic Print

Untitled #9238-e | 2011 | Todd Hido | Chromogenic Print

Though not strictly viewed as representational, directed reality involvement creatively engages the reality of the subject matter (in this case, the landscape), yet the photographer introduces a twist, which affects the reality of the view. In both Leiter’s and Hido’s works, directed reality involvement plays an instrumental role in furthering the moodiness of each narrative within the images.

Works Cited

Cole, Teju. “Postscript: Saul Leiter (1923–2013)”. The New Yorker. n.d.

Web. 4 Nov. 2017.

< http://www.newyorker.com/books/page-turner/postscript-saul-leiter-1923-2013>.

George, Michael. Workprints; Spoken Words: Todd Hido—A Road Divided; 2009; n.d., Web. 6 Nov. 2017.

<http://www.michaelgeorgephoto.com/blog/?p=361>.

Szmulewicz, Roger. Fifty One; Saul Leiter; Fine Art Photography, 2014. n.d.

Web. 5 Nov. 2017. <http://www.gallery51.com/index.php?navigatieid=9&fotograafid=15>.